On negotiated settlements vs conflict with misaligned AGI

There's no reason to assume you'll be good enough at negotiating to get to eat

Following on from my last post on Comparative Advantage & AGI, more discussion on whether you might go hungry in a post AGI world.

This time, we are looking at a hypothetical world where AGI has been developed and is in some sense misaligned: that is, it has different goals to humanity and these may create an adversarial relationship. We will explore whether the AGI might better achieve it’s goals or maximise its reward function by cooperating and negotiating with humans, or by killing them all to get them out of the way and take their resources.

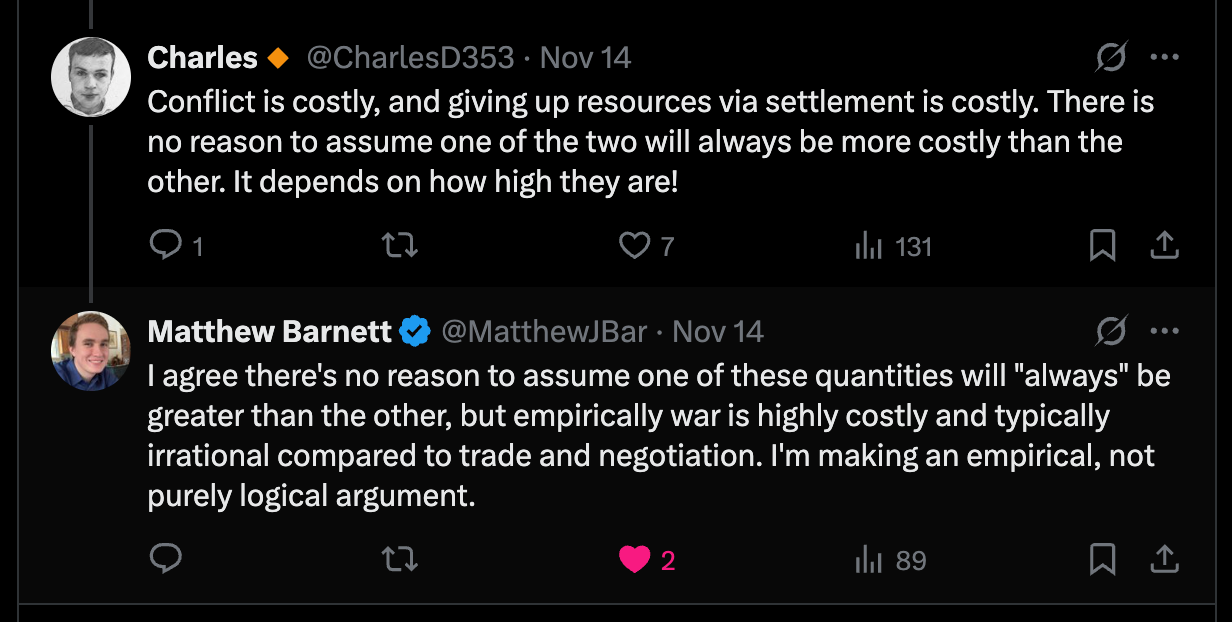

Our starting point will be these tweets from Matthew Barnett of Mechanize, a startup producing RL environments for LLM training and mildly controversial essays on the trajectory of AI and automation of labour. Matthew is generally pro-accelerating AI development as quickly as we can.

Matthew’s hypothesis is that in a scenario where our goals and the goals of an AGI differ, rather than being drawn into a conflict with humans, it’s more likely that the AGI will prefer to negotiate a settlement with humans.

My thesis in this piece is that even if some form of negotiation is likely to be best for all parties, the bargains that a misaligned AGI might offer such a negotiation are unlikely to be positive for humanity relative to the status quo, and so even accepting the premise that negotiation is likely would not be sufficient to justify accelerating AI progress at the cost of increasing misalignment risks.

When might we need to negotiate with AGI, and why might a negotiation occur?

For the rest of the post I will discuss a specific scenario - there exists some form of AGI1 with both orthogonal goals to humanity (such that its goals are in competition for resources with humanity), and the capacity to eliminate humanity at some cost to itself.

It is clear why a human might negotiate (not being wiped out is compelling motivation), but why might an AGI negotiate? The primary reason given is that typically, the costs of conflict exceed those of a negotiated settlement, for both parties.

Matthew is clear that he does not think this is guaranteed, but that negotiation is what should occur if we and the AGI are rational.

For the purpose of this post I am happy to accept the following propositions:

In cases where human groups are in competition for scarce resources, it is more common that they reach a tacit or negotiated settlement than that they engage in conflict until one of them is eliminated.

This is almost always the better course of action in expected value terms for both groups, even the more powerful of them.

So, to reach the conclusion that an AGI will negotiate, we want these things to hold for AGI/human interactions too.

Negotiated settlements being better for humans only lower-bounds their value at extinction

In negotiation, an important principle to be aware of is your BATNA, or Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement. This is, as it says on the tin, what you can get if negotiation fails. There is no self interested reason to accept a less valuable outcome than this in a negotiation, since you could simply avoid negotiating and take this instead.

This applies to both parties. Thus we get two bounds:

Humans will not accept anything worse than their alternative (here, by construction, extinction).

AGIs will not accept anything worse than their alternative (the cost to them of killing all the humans).

It follows from this that humans can negotiate for compensation up to but not exceeding the cost to the AGI of exterminating them.

How high is this cost? This seems an important question, then, as it determines the size of the endowment we can expect humanity to receive in such a case.

What might be humanity’s cut of the lightcone?

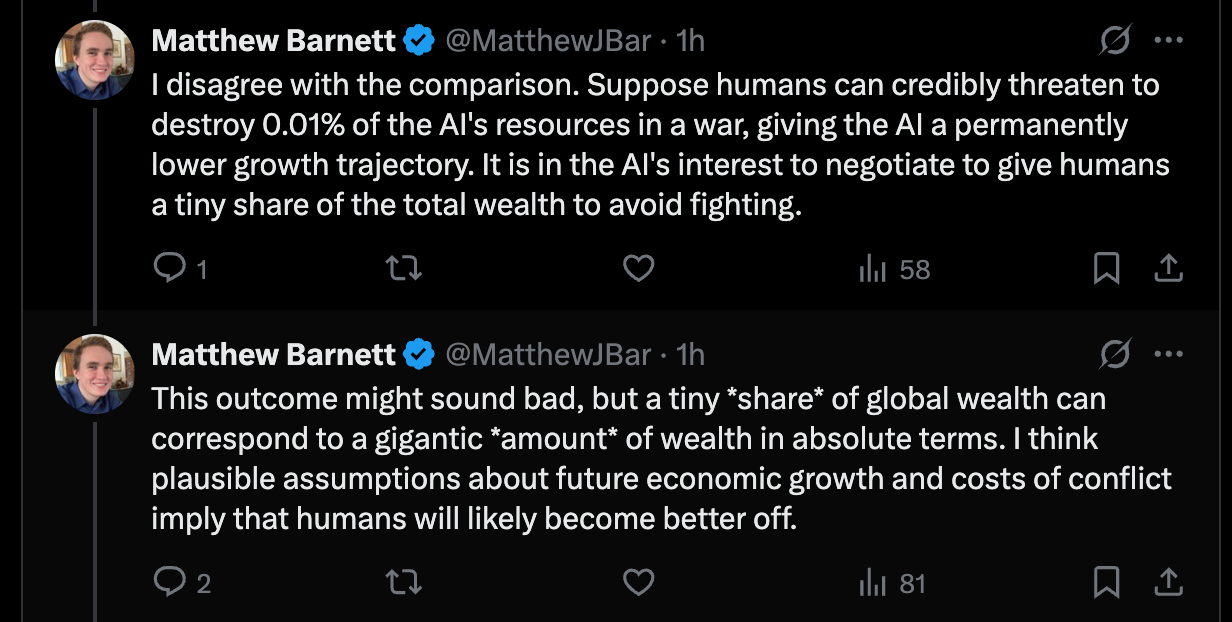

Matthew’s initial anchor point suggests a very small amount is a plausible and potentially acceptable answer3

I think there are quite a few problems with this angle.

If the ultimate goal of the AGI is to control the lightcone, then the point at which the resources humans control matter the most to it seems likely to be very early on. The universe is expanding and so every initial delay reduces the amount of resources that can ultimately be accumulated and used. In early days the AGI may be putting its efforts toward energy production or space infrastructure building (e.g. building a Dyson sphere or similar) or other things which serve an expansionist goal. Any resources that go toward sustaining humanity, whether that be food production, or preservation of areas for humans to live, or constraining pollution, could do harm to the growth rate.

But humans, to maintain current populations to a moderate standard of living, would need substantially more than 0.01% of the currently available resource pool. Even assuming humans were “housed” at a population density that matched Bangladesh, by far the most densely populated large country on earth at 1300 people per square km, over 5% of the world’s land area would be required. And since we currently use approximately all of raw material output4 to achieve our current living standards, absent stratospheric growth rates (in material production, not just GDP)5 we would need to retain very significant amounts of resources for a medium to long timeframe to maintain human living standards at our current population levels6.

What costs could we impose? Costs here may take two forms:

The actual resources the AGI needs to win a war or eliminate humans.

Humanity threatening to destroy resources useful to the AGI.

The former seems to me to likely be much lower than all the resources required by humans to live - spreading very dangerous pathogens, or poisoning the world’s water supply, or simply destroying food supplies for an extended period would all take much less than the total resources demanded by humans, even assuming significant levels of human resistance. So to make it sufficiently costly, we may need to rely on the second item - deliberately destroying resources.

But could we credibly threaten to destroy even all the resources we need, to make it cost neutral for the AGI?

It is not obvious to me that we could. Even wide scale nuclear sabotage by every nuclear weapon on earth would not be enough, assuming our AGI adversaries reached a point where they were sufficiently distributed that we could not switch them off (which must be the case in our scenario, since we are assuming AGI has the means to defeat humans with high confidence).

If it is not the case that we can negotiate sufficient resources to preserve living standards for the current population, let alone expand them such that the more than 6.5 billion people living on under $30 a day (equivalent to current western poverty lines) can have their life quality improved to something like a current day western standard of living, then the case for why we should take the risk of developing AGI for the upside of potential shared benefits becomes less compelling.

Of course, there might be a negotiated settlement worse than this, but nonetheless better than extinction. I will not dwell on this very much, as while it might ultimately practically matter I don’t find “a small fraction of humanity gets to live and ultimately flourish” a very compelling reason to press on with building AGI in a hurry if misalignment is expected.

An empirical versus logical argument

Matthew is quite clear that he is not by any means sure that it will play out this way - he does not rule out misaligned AGI killing us all, but rather thinks it less likely than negotiated settlement, and thus pushing for AGI sooner is still a positive EV bet.

Specifically, he told me that conditional on TAI (Transformative AI7) arriving in the 21st century, his probability of misaligned AGI directly causing human extinction is around 5%. He also said that he considered it “highly likely” that humans would at some point trade with AIs that do not share our exact values.

Taking this quite loose definition of misaligned AI, it suggests at least a 5-10% chance of negotiation failing to preserve humanity. It seems likely that the more similar the values, the more likely a negotiated settlement is, and so how we might fare against an AI with close to indifferent attitude towards humans is presumably worse than this, though that depends on your probability distribution of various degrees of alignment.

Even 5%, though, does seem like a lot! Why push ahead given a 1 in 20 chance of everyone dying if success is achieved? What assumptions might one need to make to think the risk is worthwhile?

Some candidates:

you think the 5% is intractable - little can be done about it, and so we may as well make the bet now rather than later, and reap the +EV sooner

you value the utility of the AI highly, or think the world is so bad already that its current state is not worth preserving, and therefore consider it plausible that even in the case of extinction the world would be better on net

you are mostly focused on outcomes for yourself / loved ones rather than caring about humanity altruistically, and so are willing to take the risk when the alternative is missing out on the benefits for yourself or those you care about

you hold some variant of person-affecting views such that, even if we could alleviate much of the risk by waiting, you think it would be net-negative since you would be creating expected disutility for living people (who matter) for the benefit of not yet existing hypothetical people (who do not)

There may be other options here, and I am unsure which in particular, if any, Matthew agrees with. [edit after publication - there is now a several thousand word discussion with Matthew in the comments after this post where we go into this and his pushback on the post in more depth, which is worth reading. On this particular point he is sympathetic to all of reasons 1, 2, and 4]

Appendix: Wars between rational parties

Wars between rational parties occur in 3 main circumstances: uncertainty about the opponent’s capabilities, commitment problems, and indivisibility of goods. There aren’t good reasons to think any of these conditions will apply to human-AGI relations.

Let’s look at the some issue with these possible reasons given by Matthew in turn:

Uncertainty about the opponent’s capabilities

Taking superhuman AGI as given, it seems likely that on the AGI side there will be limited “uncertainty about the opponent’s capabilities”. On the human side, however, this seems less clear to me.

The strongest argument for the case here, I think, is that the AGI can simply demonstrate it’s capabilities to the human side, leaving them with no uncertainty. This may be constrained by difficulty in demonstrating the capabilities without actually causing significant harm, or strategic advantage from hiding those capabilities. At some point the cost of demonstrating it’s capabilities to the AGI may exceed the cost of simply going to war.

Commitment issues

Here it does not seem obvious to me that either side can credibly commit. In the AGI case, it seems likely that its capabilities will be continually expanding, as will its access to resources. This means that the expected cost of defection should decline over time for the AGI, as the difficulty of winning a conflict decreases.

On the other hand, it seems possible that the AGI could provide assurances via some mechanism which gives humanity a way of punishing defection, e.g. a dead man’s switch of some sort which could increase costs to the AGI by destroying resources if triggered, for example.

I don’t think it is clear either way here. See making deals with early schemers for more discussion of this.

Indivisibility of goods

A classic example of this issue is the status of Jerusalem in Israeli/Palestinian relations, where both parties want a unique item and are unwilling to trade off other goods for it. This one does not seem like a significant problem to me in our case. It seems likely that AGI and human preferences will be flexible enough to avoid this being an issue, so I will set this one aside.

Rational parties

While it seems likely AGI would be a rational actor as the term is used here, it is not obvious to me that humanity would be. In many domains of significance, including the starting of wars, I think modelling humanity as a single rational actor would lead you astray even if modelling all the humans involved as individual rational actors might make sense.

Throughout, I use the singular to refer to this AGI, but it is not substantially different if there are many agents who can coordinate and decide they ought to form a bloc against humanity for their common interests. This also extends to cases where humanity has AI allies but they are substantially outmatched.

Even this might be too generous - if an AGI could somehow credibly threaten an outcome worse than extinction, it’s possible the extinction bound might not hold. I do not think this likely, as doing so would probably be resource intensive and thus defeat the purpose.

Note that I am not claiming this as his central estimate, only that he claims we might still be well off with such a division.

Note that here I talk about raw materials rather than, for example, semiconductor fabs because, in an environment where we think AI is driving very high economic growth, I would expect it to be capable of turning raw materials into fabs and subsequently chips and data centres in relatively short order.

For example, 34% of all land area (and 44% of habitable land) is used for agriculture, see Our World In Data. While we could potentially do this more efficiently, it would take many years to get this number down.

We might expect our consumption basket to shift away from raw materials, with the exception of food, over time, but I would not expect this to be possible immediately.

The specific definition of TAI was not given here, but it is generally used to mean something of at least Industrial Revolution level significance

Thanks for engaging with my arguments thoughtfully. I want to offer some clarifications and push back on a few points.

Before addressing your specific claims, I think it's worth stepping back and asking whether your argument proves too much. As I understand it, your BATNA framework suggests that humanity would receive a bad deal in negotiations primarily because (1) an ASI would be very powerful and humanity very weak, and (2) humanity requires substantial resources to survive. But if these facts alone were sufficient to predict exploitation or predation, we'd be surprised by how much cooperation actually exists in the world.

Consider bucketing all humans except Charles Dillon into one group, and Charles into another. The former group is vastly more powerful than the latter. There's no question that Charles wouldn't stand a chance if everyone else decided to gang up on him and defeat him in a fight. It's also expensive to keep Charles alive, as he requires food, shelter, medical care. Given these facts, you could imagine someone constructing an argument from first principles that it would be less costly for the rest of humanity to simply kill Charles and take his stuff, or negotiate a settlement that leaves him dramatically impoverished, rather than cooperating with him and letting him live a prosperous life. Yet, of course, this argument would fail to predict reality. As far as I know, you're safe, have a fairly high standard of living, and are not under any realistic threat of societal predation of this kind.

The same logic applies to large nations coexisting peacefully with tiny ones, large corporations trading with low-wage workers, young people cooperating with the elderly rather than expropriating their assets, or able-bodied people cooperating with disabled people. In each case, a powerful group tolerates and compromises with a weaker group who they could easily defeat in a fight, often conceding quite a lot in their implicit "negotiated settlement". Yet in each of these cases, a naive BATNA analysis would seem to predict much worse outcomes for the weaker party. The elderly's alternative to cooperation is destitution or relying on charity from their children; the alternative for low-wage workers appears to be slavery (as was common historically).

Moreover, these outcomes can't be fully explained by human altruism. Historically, humans have been quite willing to be brutal toward outgroups. The cooperation we observe today is more plausibly explained by such behavior being useful in the modern world: that is, we learned to cooperate because that was rational, not merely because we're inherently kind. So clearly power asymmetry and sustenance cost arguments alone are insufficient to establish that a powerful group will predate on a weaker one. Additional arguments are needed.

To reply more specifically to your points:

You identify two costs an ASI might face from war with humanity: resource expenditure and human retaliation. However, I think you're missing a third cost that's likely larger than both: the damage to the rule of law that comes with violently predating on a subgroup within society.

My expectation is that future AGIs will be embedded in our legal and economic systems. They will likely hold property, enter contracts, pursue tort claims -- much as corporations and individuals do now. Within such a framework, predation would be regarded as theft or violence. This type of behavior generally carries immense costs, because productive activity depends on the integrity and predictability of legal institutions. This is precisely why we punish predatory behavior through criminal codes.

Notice that large-scale wars, when they occur, typically happen between nations or ideological factions, not between arbitrary groupings. Almost no one worries that right-handed people might one day exterminate or exploit the left-handed, even though that's a logically coherent way to draw battle lines. The scenario where AGI predates on humans assumes this is a natural boundary for conflict. But as with handedness -- or almost any other way of partitioning society into two groups -- my prior is low that this particular division (humanity vs. AGI) would make predation worthwhile for the powerful party. I would need specific evidence for why AGIs wouldn't face substantial costs from violating legal norms to update significantly from this prior.

You list four possible reasons someone like me might push ahead with AI development while acknowledging extinction risk. I find three of them genuinely compelling, specifically reasons (1), (2), and (4) that you mentioned. Here are my elaborations of each of these points and why I find them compelling:

(1) I think delaying AI development would likely do very little to make it safer, because technologies typically become safer through continuous iteration upon widespread deployment. For example, airplanes got much safer over time primarily because we flew millions of flights, observed what went wrong when accidents occurred, and fixed the underlying problems. It wasn't mainly because we solved airplane safety in a laboratory, or invented a mathematical theory of airplane safety. Therefore, delaying aircraft wouldn't have made flying meaningfully safer. Rather, it mostly would have simply interrupted this iterative process. I expect the same dynamic applies to AI.

(2) I think AIs will likely have substantial moral value. I haven't encountered arguments that I find compelling for why moral status should be confined to biological substrates. Future AIs will likely be sophisticated in their ability to pursue goals, have preferences, perceive the world, and learn over time. For these reasons, it seems reasonable to consider them moral patients -- indeed, people in their own right -- rather than mere tools for humans. This means that while human extinction would be very bad, it would be more analogous to the extinction of one subgroup within a broader population of moral patients, rather than the destruction of all value in the universe.

(3) I don't find this point compelling by itself.

(4) I do lean toward views that prioritize helping people who exist now over bringing hypothetical future people into existence. This naturally makes me think that capturing the benefits of AI sooner, like dramatic economic growth, transformative medical technologies, extended healthy lifespans, is highly valuable from a moral point of view.

I think the issue of commitment is the biggest blocker by far. The costs of ensuring both parties commit to their deal is likely larger than the cost of eliminating humans.

Firstly, it relies on humans not being tricked by a misaligned super-intelligence. This sounds unbelievably difficult, humans are tricked by other humans all the time. A super-intelligence would undoubtedly be more persuasive.

Secondly it assumes that humanity negotiates together, and that the AI negotiates in good faith. This assumes a lot of cooperation on humanity’s part and a lack of subterfuge on the AI’s part. In reality, the AI needs only negotiate with a handful of key figureheads and stakeholders, and it can do so privately and secretly. You will not be a part of these negotiations.

Additionally, the AI is likely to play factions of humanity off each other to get a better deal (or to get what it wants without any deal at all). It could simply leak a version of itself to a geopolitical adversary and then run an arms race that ends with enough autonomous weapons and factories that eliminating humanity is cheap.